We, the family Complojer.

Riposo al Bosco is and will remain a family-run hotel – today, however, with a clear modern vision and the standards of a contemporary 3-Star Superior property.

Following a significant generational transition, the hotel is now led by Simon Complojer and Giovanna Lastella, who combine tradition and genuine hospitality with fresh ideas, new energy and a modern understanding of quality. Supported by their family and a dedicated team, they have created a place where personal attention, authenticity and professionalism go hand in hand.

What truly sets us apart is our closeness to our guests: short distances, sincere warmth and a genuine sense of welcome – complemented by modern comfort, well-organised processes and a clear focus on the future.

What was once a traditional inn has evolved into a modern hotel that honours its roots while embracing the spirit of a new generation – family-run, thoughtfully reimagined.

During the 2018/2019 season, Riposo al Bosco was struck by a profound and unexpected loss: the sudden passing of Simon Complojer’s mother. This moment marked not only a deep personal tragedy, but also a significant turning point in the history of the hotel.

From that moment on, Simon Complojer and his wife Giovanna Lastella jointly took over the management of the property. A great responsibility, and at the same time the beginning of a new chapter for Riposo al Bosco. With respect for the past and a clear vision for the future, this transition gave rise to a new story that continues to shape the spirit and identity of the hotel today.

Holiday in the Alps.

The present owner’s parents were the ones who established our hotel back in the 50ies, at a very difficult time for the South Tyrolean people. The time after the Second World War was everything but easy and hit our little region hard. Many Tyroleans impoverished and emigrated. Tourism in the area was just starting to become established. Between the years of 1939 and 1943, the South Tyrolean people were given the choice to either leave their homes and move to Austria or Germany or stay at home and become ‘italianized’. Later, when the war had ended, uncertainty about the future of the region caused great anxiety among the South Tyroleans. Many returned and hoped to regain the Italian citizenship. An agreement between the Austrian minister Karl Gruber and the prime minister of Italy made this possible. The same agreement also laid the foundations for the wealthy South Tyrol we experience today. Our parents seemed to have had the right instinct.

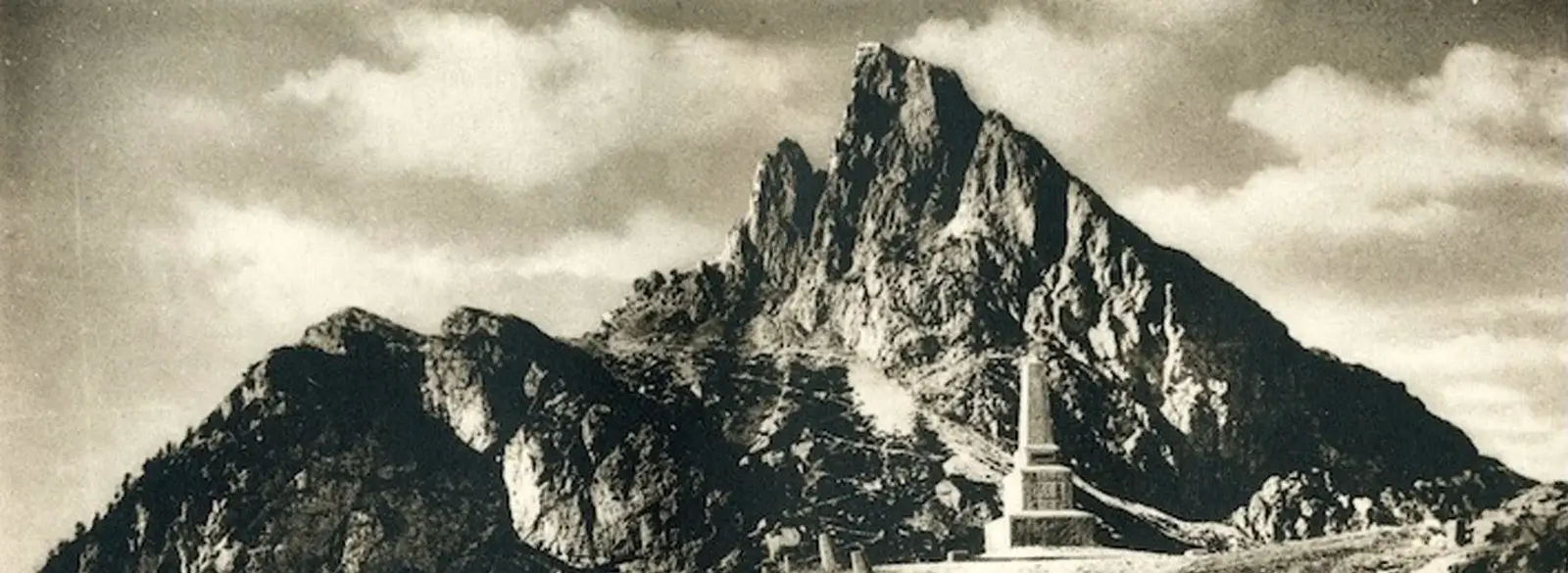

The pass of Falzarego.

San Vigilio and its surroundings have been fascinating people for centuries and have led to the creation of its very own mythology. One of the most famous stories is about the brave king’s daughter Dolasilla, a war hero of the Fanes people. Her father, a greedy man, had stolen some precious objects from a group of dwarves which Dolasilla returned to them without her father’s knowledge. In return for that, she was given a white armor which would protect her from arrows. The dwarves also predicted that Dolasilla was to become a war hero and that she should not go to war if her armor ever turned dark. They also told here that something mysterious was growing in the Silver Lake. Her father then sent messengers to this lake to have a look. There, they found silver reeds from which silver arrows were made. With these arrows, the Fanes people never lost a war again. Dolasilla was awarded with a precious stone called the “Rajëta”. One night, Dolasilla had a dream where she saw one of her dead enemies warning her of continuing to fight with the silver arrows. The king, however, insisted that Dolasilla should keep using them. In the meantime, the wizard Spina de Mul forged an alliance against the Fanes realm. He wanted to steal Dolasillas precious stone. He hired the hero Ey de Net, “night eye”, who should kill Dolasilla in their next battle. Ey de Net, however, was so impressed by the king’s daughter, that he shot no arrow at her. Spina de Mul betrayed him by shooting an arrow behind Ey de Net’s back. The latter felt betrayed and switched sides. He became the shield bearer of Dolasilla and even asked for her hand in marriage. But the king knew about a prophecy stating the Dolasilla would lose all her battling power if she was ever married. Out of greed, the king sold his realm to his enemies and banished Ey de Net. Dolasilla, unwittingly, gave away all her silver arrows to children sent by Spina de Mul and had to leave for a battle shortly afterwards, even though her armor had turned dark. It was in this battle, that Dolasilla was killed. Her father, who received the news while he was waiting on the Lagazuoi, turned into stone. He, the “treacherous king”, “falza rego”, can still be seen on the pass of Falzarego.

Holidays in the mountains.

South Tyrol is one of the most prosperous regions in Italy and Europe. It is best known for its beautiful mountain landscape, which attracts countless tourists every year. However, tourism in this small Alpine region only developed gradually over time. For a long time, the Alps, instead of being a popular travel destination, were more of an impassable obstacle on the way to sunny Italy. Around 1800, when the South Tyrolean Andreas Hofer led a Tyrolean uprising against Napoleon, the region first gained widespread recognition throughout Europe. Tyrol had already been a popular health resort for some time, albeit only among the wealthy upper class. Every summer, rich merchants from the cities in and around Tyrol would retreat to the mountains for their summer holidays. The first real peak in tourism in South Tyrol occurred shortly before the beginning of the 20th century. Foreign investors began building large hotels in places like Toblach. Mountaineering also became increasingly popular, benefiting mountain pastures and refuges in particular. South Tyrol first became a picture-postcard destination in the years leading up to the First World War. These years were characterized by luxurious hotels and lavish parties for high society. Mass tourism in the region only began later, after the First World War, when South Tyrol became part of Italy. Italians flocked to visit the region. Around 1930, the development of the Dolomites for tourism purposes finally began. Cable cars, restaurants, and mountain hotels – all of this dates back to this period. In the years after the Second World War, many families began renting out rooms to tourists. After that, tourism in the region grew rapidly. Then, with ski star Gustav Thöni, skiing became even more popular, and new ski lifts and resorts were built. And right in the midst of this eventful history – our Hotel Riposo al Bosco.